Trigger warning: this post discusses miscarriage, and highly personal aspects of women's healthcare.

As I write this I’m recovering from what my healthcare provider alarmingly referred to as a MAJOR PROCEDURE. The language, not to mention the all-caps, is hardly consistent with what my doctor assures me is “probably nothing.” But alas, the medical and insurance establishments don’t always use the most helpful language. (A friend of mine is pregnant with her second child. She is also forty-five years old, making hers a “geriatric” pregnancy.) When I log on to my account for details, I am informed that I have an upcoming MAJOR PROCEDURE! I received emails reminding me I am scheduled for a MAJOR PROCEDURE!

Another name for my procedure is hysteroscopy. “Oscopy” is probably familiar to many of a certain age, as in a colon-oscopy, it means viewing, normally with a scope. Hyster is the Greek word for womb, which is why I try to avoid the word hysterical. Though hysterical means, broadly, “out of control emotionally,” there’s some sexism baked into its etymology. My hysteroscopy came about when an ultra sound for an unrelated issue revealed something called a “possible echogenic lesion” in my uterus. Echogenic sounds good, vaguely audio. Possible is nice and mild. Lesion, not so much. “Sometimes these things are nothing,” I’m told by the forthcoming ultrasound technician. “Just scar tissue,” she says, “or even a blip in the ultrasound.”

“Scar tissue?” I ask. “Could it be scar tissue from a miscarriage?”

“Could be,” she says with a detached, noncommittal air. “I’m not a doctor. But don’t worry. Sometimes they get in there and they don’t find anything.”

They get in there?

When I do talk to my doctor she is reassuring. Here’s where the “probably nothing” idea is introduced. This is the language I use when I talk to my mother, who is a World Champion Worrier. “Still,” the doctor says, “we want to go in and have a look around, and if there’s anything in there, we’ll take it out.” Let me assure you that hearing this is nothing at all like when you ask the rodent proofers to inspect your basement and take care of any problems, or invite the Salvation Army to help themselves to the contents of your garage. This is my uterus they’re talking about! I resist a strong impulse to say “thanks, I’m good,” as if someone is passing by with a platter of unappetizing canapés. Instead, I agree to have the procedure.

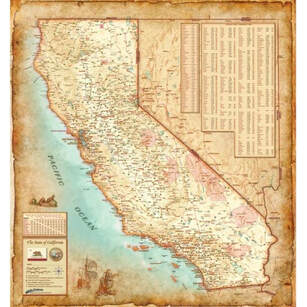

Throughout this experience, I’m aware of my privilege. I have relatively good healthcare, for which I pay an outrageous sum, but at least I’ve got insurance. I’m menopausal so there are no pregnancy-related issues, and even if there were, I’m in the state of California, which for now at least, gives me rights women in other states don’t have. There are no issues here aside my personal well-being. I interview two doctors for this procedure, one who wants me to go to a huge hospital in San Francisco and be sedated, and one who will do the procedure in office, without anesthesia, here in Berkeley. “If you can take it,” the second doctor says.

I take option B, even though I know my pain threshold is lower than the water table in Death Valley.

As I write this I’m recovering from what my healthcare provider alarmingly referred to as a MAJOR PROCEDURE. The language, not to mention the all-caps, is hardly consistent with what my doctor assures me is “probably nothing.” But alas, the medical and insurance establishments don’t always use the most helpful language. (A friend of mine is pregnant with her second child. She is also forty-five years old, making hers a “geriatric” pregnancy.) When I log on to my account for details, I am informed that I have an upcoming MAJOR PROCEDURE! I received emails reminding me I am scheduled for a MAJOR PROCEDURE!

Another name for my procedure is hysteroscopy. “Oscopy” is probably familiar to many of a certain age, as in a colon-oscopy, it means viewing, normally with a scope. Hyster is the Greek word for womb, which is why I try to avoid the word hysterical. Though hysterical means, broadly, “out of control emotionally,” there’s some sexism baked into its etymology. My hysteroscopy came about when an ultra sound for an unrelated issue revealed something called a “possible echogenic lesion” in my uterus. Echogenic sounds good, vaguely audio. Possible is nice and mild. Lesion, not so much. “Sometimes these things are nothing,” I’m told by the forthcoming ultrasound technician. “Just scar tissue,” she says, “or even a blip in the ultrasound.”

“Scar tissue?” I ask. “Could it be scar tissue from a miscarriage?”

“Could be,” she says with a detached, noncommittal air. “I’m not a doctor. But don’t worry. Sometimes they get in there and they don’t find anything.”

They get in there?

When I do talk to my doctor she is reassuring. Here’s where the “probably nothing” idea is introduced. This is the language I use when I talk to my mother, who is a World Champion Worrier. “Still,” the doctor says, “we want to go in and have a look around, and if there’s anything in there, we’ll take it out.” Let me assure you that hearing this is nothing at all like when you ask the rodent proofers to inspect your basement and take care of any problems, or invite the Salvation Army to help themselves to the contents of your garage. This is my uterus they’re talking about! I resist a strong impulse to say “thanks, I’m good,” as if someone is passing by with a platter of unappetizing canapés. Instead, I agree to have the procedure.

Throughout this experience, I’m aware of my privilege. I have relatively good healthcare, for which I pay an outrageous sum, but at least I’ve got insurance. I’m menopausal so there are no pregnancy-related issues, and even if there were, I’m in the state of California, which for now at least, gives me rights women in other states don’t have. There are no issues here aside my personal well-being. I interview two doctors for this procedure, one who wants me to go to a huge hospital in San Francisco and be sedated, and one who will do the procedure in office, without anesthesia, here in Berkeley. “If you can take it,” the second doctor says.

I take option B, even though I know my pain threshold is lower than the water table in Death Valley.

When I first go into the procedure room, I undress and put on a large paper blanket. I am sitting on the – what is it, a table? A chair? A chaise lounge? The thing with the stirrups. I see that at the end of it, there is a large clear plastic bag stretched open. It reminds me of an all-clear raincoat I had when I was a little girl. I know its purpose. It is there to catch whatever falls out of me. I am immediately connected to my experience of a miscarriage more than twenty years prior, and to all women who go into rooms like this, and sit waiting, wearing thin paper blankets.

As things get going, I begin to have concerns. I will struggle not to be too graphic here, but in order to go into the uterus to look around, they’ve got to, well, open things up. This involves something called a speculum, which sounds a lot like the name of a sweet Dutch treat. But a speculum is much less fun, trust me. This procedure also involves getting shots. Shots using needles, um, internally. I think lidocaine is mentioned, but I’m not sure. I’m getting light headed. The pain is ridiculous. There are three women in the room with me. The doctor and two nurses. Only one nurse is assisting the doctor. The other is a professional hand holder. I worry I might break her fingers. The doctor adjusts the table so that I am somewhat upside down which makes me even dizzier. Given the context, this is not a bad thing.

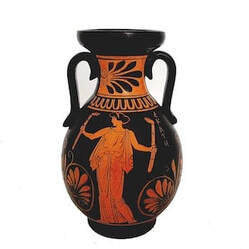

Next to the hand holder is a tv screen. After the pain portion of the program subsides, I open my eyes and watch the scope moving around. I’m seeing my insides, kind of like the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage, in which Raquel Welch and a submarine crew shrink down to size and go exploring inside the human body. For a while my ringtone was Lakeside’s Fantastic Voyage, a funk classic that grooves along with the lyrics “Slide slide, slippety-slide, just forget about your troubles and your nine to five.” But this is not like Raquel Welch in a miniature submarine, nor a funk dance classic. It’s amazing, but not fun. I see a combination of white and pink that looks quite extraterrestrial if I’m honest. A galaxy inside of me. I decide I’ve seen enough. I prefer to retain my previous image of my uterus, which is something like an elegant, two-handled vase, possibly a Roman amphora, or an urn Keats would approve of. It's the kind of vase one might fill with nectar, and place at the oracle to please the gods, or more likely, the goddesses.

I close my eyes.

Though I’m not on anything stronger than Advil and Tylenol, I’m feeling woozy, and emotional. I am moved by the kind, competent presence of the three women supporting me. I try not to read the news too much these days, but I am vaguely aware of a batch of horror stories coming out of states where women’s uteri are under siege. Women being denied care and traveling thousands of miles at great personal expense, and risk. Doctors are confused about what they can and can’t do. I’m specifically aware of a woman in Ohio who may be criminally charged with mishandling a corpse after miscarrying at home. It is beyond gruesome. Something about my experience is opening a channel to the suffering of all women, everywhere. Whether this is empathy or narcissism, I couldn’t say.

When I miscarried, no, I apologize for the digression, but let’s not just use that shorthand, when I happily went to the obstetrician for an ultrasound of the new life growing inside of me, and was told that my baby had died before it had a chance to live, when that happened, I went through a procedure they call a D and C. No, not Direct Current. This D stands for Dilation, the C for Curettage. Similar in some ways to what is being done now, they took everything out, the dead fetus and fetal tissue. My doctor said it would make my recovery quicker, easier, and safer. Even so, my grief was so total I lay in bed for days, or weeks, I couldn’t say. While I was in bed, recovering, the Twin Towers went down. America had been attacked. It was horrific, but I remember feeling numb. It didn’t affect me, not really, until much later. In that moment, when my mom called and told me to turn on the news, it didn’t shock me. Maybe because I was already there, in the land of death and destruction. The bottom had already fallen out.

As things get going, I begin to have concerns. I will struggle not to be too graphic here, but in order to go into the uterus to look around, they’ve got to, well, open things up. This involves something called a speculum, which sounds a lot like the name of a sweet Dutch treat. But a speculum is much less fun, trust me. This procedure also involves getting shots. Shots using needles, um, internally. I think lidocaine is mentioned, but I’m not sure. I’m getting light headed. The pain is ridiculous. There are three women in the room with me. The doctor and two nurses. Only one nurse is assisting the doctor. The other is a professional hand holder. I worry I might break her fingers. The doctor adjusts the table so that I am somewhat upside down which makes me even dizzier. Given the context, this is not a bad thing.

Next to the hand holder is a tv screen. After the pain portion of the program subsides, I open my eyes and watch the scope moving around. I’m seeing my insides, kind of like the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage, in which Raquel Welch and a submarine crew shrink down to size and go exploring inside the human body. For a while my ringtone was Lakeside’s Fantastic Voyage, a funk classic that grooves along with the lyrics “Slide slide, slippety-slide, just forget about your troubles and your nine to five.” But this is not like Raquel Welch in a miniature submarine, nor a funk dance classic. It’s amazing, but not fun. I see a combination of white and pink that looks quite extraterrestrial if I’m honest. A galaxy inside of me. I decide I’ve seen enough. I prefer to retain my previous image of my uterus, which is something like an elegant, two-handled vase, possibly a Roman amphora, or an urn Keats would approve of. It's the kind of vase one might fill with nectar, and place at the oracle to please the gods, or more likely, the goddesses.

I close my eyes.

Though I’m not on anything stronger than Advil and Tylenol, I’m feeling woozy, and emotional. I am moved by the kind, competent presence of the three women supporting me. I try not to read the news too much these days, but I am vaguely aware of a batch of horror stories coming out of states where women’s uteri are under siege. Women being denied care and traveling thousands of miles at great personal expense, and risk. Doctors are confused about what they can and can’t do. I’m specifically aware of a woman in Ohio who may be criminally charged with mishandling a corpse after miscarrying at home. It is beyond gruesome. Something about my experience is opening a channel to the suffering of all women, everywhere. Whether this is empathy or narcissism, I couldn’t say.

When I miscarried, no, I apologize for the digression, but let’s not just use that shorthand, when I happily went to the obstetrician for an ultrasound of the new life growing inside of me, and was told that my baby had died before it had a chance to live, when that happened, I went through a procedure they call a D and C. No, not Direct Current. This D stands for Dilation, the C for Curettage. Similar in some ways to what is being done now, they took everything out, the dead fetus and fetal tissue. My doctor said it would make my recovery quicker, easier, and safer. Even so, my grief was so total I lay in bed for days, or weeks, I couldn’t say. While I was in bed, recovering, the Twin Towers went down. America had been attacked. It was horrific, but I remember feeling numb. It didn’t affect me, not really, until much later. In that moment, when my mom called and told me to turn on the news, it didn’t shock me. Maybe because I was already there, in the land of death and destruction. The bottom had already fallen out.

Abigail Adams, painted by Gilbert Stuart

Abigail Adams, painted by Gilbert Stuart Back in the procedure room I open my eyes and catch a blur on the TV, where the picture is changing faster. I hear a vacuuming sound. I’m being hoovered. I avert my gaze and stare at the ceiling, and start talking to take my mind of things. I tell the three women about the daughter of a friend of mine. She’s just finished med school in obstetrics, and is now pregnant with her first child. There is a swell of happiness among the three women as I describe my friend’s daughter’s love for their field. I see now that their profession, while not religious, contains an element of the sacred. A surge of real anger rises in me about the woman in Ohio. I might be really light headed at this point, because I start to imagine that there are men in the room with us. Three men in black robes, hovering around the periphery of my consciousness. Watching, monitoring, deciding. Lawmakers, maybe. Or Judges. It’s creepy. Decidedly creepy. Thankfully they begin fading, like Captain Kirk when he is beamed up. I wonder one last time who they are. What they are. The only word I can come up with, though it seems unfair to monsters, is monstrous.

For many the recovery time for this procedure, is quick. A matter of a day or two, or so I’m told. But as usual, I tend toward the delicate-flower and I am mostly in bed for four full days. During that time I am bleeding as the leftovers from my newly reopened uterus pour out of me. It is odd once again to rely on the maxi pad, to feel cramps and pain I’d almost forgotten about. And there is an emotional component as well. I need those days in bed, not just physically. I need a sanctuary. I feel vulnerable. Tender. Sad. Womanish. I keep a heating pad over my belly and won’t let the little dogs climb on me. For my viewing I choose to rewatch the superb 2008 miniseries John Adams starring Paul Giamatti as John, and Laura Linney as his wife, Abigail. There is something about watching the story of our founding fathers that resonates with the present-day politics around the abortion issue. These groups of men (it’s still mostly men) trying to decide matters, all our fates in their hands. Abigail Adams famously advised her husband to “remember the Ladies,” cautioning him not to give husbands unlimited power, and reminding him that “all men would by tyrants if they could.” Linney is always good, but this role may be the role of her lifetime. Her Abigail is expressive, yet contained. Her limitations as a woman in that revolutionary era are sharply etched, and yet she is supreme, powerful, important. “There is much women can do,” she says, “if men would let us do it.”

Abigail Adams had six children. One died at the age of two. Another, in 1777, the year after our country was born, was stillborn.

My recovery goes well. I have the week free from obligation. I have help walking the dogs. I have good food, good tv, and my heating pad. And I have the words the doctor shared with me as she finished up. (In a lot of old movies, the male doctor conspires with the husband not to tell the woman she is dying. Because you know, it would only upset her, the poor dear.) But my doctor narrates her findings in real time. The phrase that jumps out is “Completely Normal.” I don’t think I have ever been called completely normal, but now it is a complement. They found nothing. The echogenic whatever-it-was, was a blip in sound. A biopsy of the area is taken to be analyzed. Pathology will have the last word. But so far so good.

My uterus is healing. I am six days out from the procedure and still feeling a bit tender in the tummy. And while I look forward to being “all better,” I don’t want to forget the pain of this week. My connection to the female experience, the embodied Her-story, has been strengthened. But also, more individually, the old familiar pains of cramping, the fatigue of blood loss, have been a time capsule, connecting me to my younger self. Not only the miscarriage, but all those periods, all that pain, all those moods. For the first time in ages, I think of my first period and those awkward teenage efforts to survive this monthly catastrophe without humiliation. In my twenties I used to call it “hot fudge sundae night,” when the pain was unbearable and I craved chocolate (probably, I later learned, for its magnesium.) In my thirties I recall times worried about being pregnant, and many, many more times wanting to be, the bleeding arriving as both a pain and a disappointment. This younger self seems much more vulnerable than the me of today. And yet I wonder if we humans appreciate the difference between being vulnerable, and being weak. Because as my healing continues I realize something else. I am feeling a bit like Abigail Adams. I feel powerful. I got through it. Me and my uterus did it. And I’m proud of us.

The message about the pathology comes through via my healthcare’s web portal. No all-caps this time. Just a quick note from the doctor. No cancer. No pre-cancerous cells. “This is good,” she adds, for clarity’s sake.

And so I’ve taken another turn in life’s highway, safely. Something that could’ve been horrible, was not so horrible. This time. But even so, a new experience has been deposited, both in the body and also in the psyche. Right now the experience is raw, uncooked by time. I have told you to the best of my ability how the story reads to me today, but it will have to be metabolized over the years, as these things invariably are. Meanings and interpretations will loop backward to touch upon personal history, then pit-stop in the broader human experience to fuel up on collective wisdom, and eventually the whole thing will catapult forward to the Land of Truer Insight. This is the opposite of a rearview mirror. Here, objects may appear much closer than they actually are, and also quite different than when we first endured them.

For many the recovery time for this procedure, is quick. A matter of a day or two, or so I’m told. But as usual, I tend toward the delicate-flower and I am mostly in bed for four full days. During that time I am bleeding as the leftovers from my newly reopened uterus pour out of me. It is odd once again to rely on the maxi pad, to feel cramps and pain I’d almost forgotten about. And there is an emotional component as well. I need those days in bed, not just physically. I need a sanctuary. I feel vulnerable. Tender. Sad. Womanish. I keep a heating pad over my belly and won’t let the little dogs climb on me. For my viewing I choose to rewatch the superb 2008 miniseries John Adams starring Paul Giamatti as John, and Laura Linney as his wife, Abigail. There is something about watching the story of our founding fathers that resonates with the present-day politics around the abortion issue. These groups of men (it’s still mostly men) trying to decide matters, all our fates in their hands. Abigail Adams famously advised her husband to “remember the Ladies,” cautioning him not to give husbands unlimited power, and reminding him that “all men would by tyrants if they could.” Linney is always good, but this role may be the role of her lifetime. Her Abigail is expressive, yet contained. Her limitations as a woman in that revolutionary era are sharply etched, and yet she is supreme, powerful, important. “There is much women can do,” she says, “if men would let us do it.”

Abigail Adams had six children. One died at the age of two. Another, in 1777, the year after our country was born, was stillborn.

My recovery goes well. I have the week free from obligation. I have help walking the dogs. I have good food, good tv, and my heating pad. And I have the words the doctor shared with me as she finished up. (In a lot of old movies, the male doctor conspires with the husband not to tell the woman she is dying. Because you know, it would only upset her, the poor dear.) But my doctor narrates her findings in real time. The phrase that jumps out is “Completely Normal.” I don’t think I have ever been called completely normal, but now it is a complement. They found nothing. The echogenic whatever-it-was, was a blip in sound. A biopsy of the area is taken to be analyzed. Pathology will have the last word. But so far so good.

My uterus is healing. I am six days out from the procedure and still feeling a bit tender in the tummy. And while I look forward to being “all better,” I don’t want to forget the pain of this week. My connection to the female experience, the embodied Her-story, has been strengthened. But also, more individually, the old familiar pains of cramping, the fatigue of blood loss, have been a time capsule, connecting me to my younger self. Not only the miscarriage, but all those periods, all that pain, all those moods. For the first time in ages, I think of my first period and those awkward teenage efforts to survive this monthly catastrophe without humiliation. In my twenties I used to call it “hot fudge sundae night,” when the pain was unbearable and I craved chocolate (probably, I later learned, for its magnesium.) In my thirties I recall times worried about being pregnant, and many, many more times wanting to be, the bleeding arriving as both a pain and a disappointment. This younger self seems much more vulnerable than the me of today. And yet I wonder if we humans appreciate the difference between being vulnerable, and being weak. Because as my healing continues I realize something else. I am feeling a bit like Abigail Adams. I feel powerful. I got through it. Me and my uterus did it. And I’m proud of us.

The message about the pathology comes through via my healthcare’s web portal. No all-caps this time. Just a quick note from the doctor. No cancer. No pre-cancerous cells. “This is good,” she adds, for clarity’s sake.

And so I’ve taken another turn in life’s highway, safely. Something that could’ve been horrible, was not so horrible. This time. But even so, a new experience has been deposited, both in the body and also in the psyche. Right now the experience is raw, uncooked by time. I have told you to the best of my ability how the story reads to me today, but it will have to be metabolized over the years, as these things invariably are. Meanings and interpretations will loop backward to touch upon personal history, then pit-stop in the broader human experience to fuel up on collective wisdom, and eventually the whole thing will catapult forward to the Land of Truer Insight. This is the opposite of a rearview mirror. Here, objects may appear much closer than they actually are, and also quite different than when we first endured them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed