What’s the first thing you think of when you think of the Cold War? If you’re American, chances are good that your first thought is an image provided by the media, whether film, television, or newspapers. Depending on your age and political orientation, you might flash on Kennedy standing on the steps of city hall in Schöneberg in ’63 saying “Ich bin ein Berliner,” or Reagan at Brandenburg Gate in ’87 saying, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.” Or you might remember newsreel footage of the Cuban missile crisis, or Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove.

As of next week, we’ll have another image for the pile. A blockbuster starring Tom Hanks and directed by Steven Spielberg, titled Bridge of Spies.

One nice thing about being a movie fan these days, is that we can see how movies have lives over time. As they stay the same, we watch and re-watch them, seeing how we change around them. Eventually, they may look dated, silly, or even offensive. Alternately, they may point so directly to something we have continued to ignore, we are shamed by their prescience.

Where Bridge of Spies will fall, time will tell.

About a year ago, I began researching a novel that I intend to set in East Berlin in the 1980’s. But I soon found that to understand Berlin in the 80’s, one must understand Berlin in the 70’s, and the 60’s, and that, in fact, if you want to understand the Cold War, you need to understand the hot ones that preceded it. This is a zone writers can get stuck in, as researching becomes its own, fascinating form of procrastination. I finally have made it back to the 80’s, but on the way there, I read a few books that circle the subject matter of an upcoming blockbuster film, Bridge of Spies, so it seemed like a good time to discuss them, almost as a prophylactic, before the film takes its place in your mind as a definitive image of these events. It is not a matter of how much one loves books, or how much one loves movies. It’s just how it is. Once you’ve seen the movie, it becomes very difficult to dislodge the images. I read all the Harry Potter books, but now, Daniel Radcliff’s is the face I see when I think of Harry.

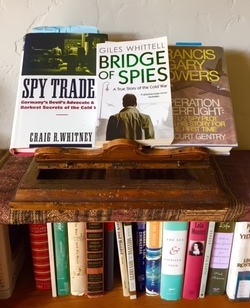

The plot of the upcoming film deals with the downing of a U2 spy plane over Russia, the subsequent capture of its pilot, Francis Gary Powers, and his exchange for a prisoner held in the States, a Russian operative working in the U.S. under multiple aliases, one of which was Rudolf Abel. Hanks plays American lawyer James Donovan, who helped negotiate the exchange. Publicity for the film, with script by Matt Charman and Joel and Ethan Coen, does not credit the first book on my list as a source, though it shares the same title, and subject matter.

Giles Whittell’s non-fiction book, Bridge of Spies A True Story of the Cold War tells the twin tales of Powers and Abel leading to one of the most iconic events of the Cold War, when the two were traded for one another at a popular locale for such swaps, the Glienicke Bridge, which spans the Havel river and connects the Wannsee district of Berlin (under western control during the cold war) with Potsdam (under the control of Eastern Germany at the time.)

Mr. Whittell is Washington correspondent for The Times, and this book is written in straightforward, journalistic prose that reads like a thriller because it is one. If you read on of the three on this list, this is the one.

One of the most troubling points in my research was interviewing a man who had been a high-ranking police officer in East Berlin during the 70’s and 80’s. A criminal investigator for the Volkspolizei. One point he made repeatedly when we spoke was that in the 80’s, they closed all of their cases. All of them, he emphasized proudly. Well, they had informants, both paid and coerced by other means, in every building, pub, workplace and neighborhood in Berlin. They could arrest anyone they wanted for any reason at any time. Of course they closed their cases! But the man, now around seventy, wasn’t exactly boasting. What I came to realize was that he was trying to convey to me that the department was an efficient one. I was an author, asking specific questions about training, development, and execution of the law in practical terms. And he was a professional, proud of the work he did. Of course I empathize with the oppression that was endemic at this time, and we all know of people imprisoned for their beliefs or opposing the government. But human beings commit all kinds of crimes, and there’s no reason to believe that rapists and murderers and thieves disappeared during the Cold War. I had never given much thought to this man, and others like him, who were the ones tracking those people down, facing all the usual difficulties and dangers of police work as the war raged on. Yes, they were an arm of the MfS (Ministry for State Security, or Stasi) but they also had a job to do- or try to do- within their own oppressive system.

The man I spoke with seemed to me somewhat heartbroken that this work had not, in the end, meant, in the end, what he’d hoped it would mean for him. He was strapped financially, had lost his sense of position almost entirely. Twenty-five years after the fact, I think he was still confused by it all, disoriented even. Meeting him was a great reminder to me that important players in history are still human beings. Complex, often conflicted, not easily summarized or pigeon-holed.

One such complicated character, a looming presence in East Germany during the Cold War, and perhaps the best subject of study for those who want a comprehensive sense of the swapping of prisoners throughout the entirety of the era, was Wolfgang Vogel, the East German attorney who brokered most of the important prisoner exchanges, including that of Powers and Abel. (He’ll be played by Sebastian Koch, a German film star American audiences may remember from the film Das Leben des Anderes.) Vogel, like my Policeman, was vilified when the wall came down, but his day-to-day life seems mostly to have been that of a hardworking advocate, capitalizing on the East German government’s poverty to negotiate freedom for some of its most coveted prisoners, which is to say, some of its most oppressed citizens. Spy Trader: Germany’s Devil’s Advocate and the Darkest Secrets of the Cold War by Craig R. Whitney is absolutely crammed with dangerous close calls, nefarious political maneuvers, and nuts and bolts of thousands of exchanges that kept the nearly bankrupt regime from crumbling sooner than it might otherwise have done. Vogel is the main character study, and his counterpart, Donovan, also figures prominently. For a lawyer, or anybody interested in the law, this is a fascinating book.

During the Cold War, information was closely guarded on both sides. In London in the 80’s, underground booksellers would sidle up to someone and whisper: “Spycatcher,” because the book had been banned in the U.K. Even though these days we are overloaded with information, then as now, there are moments that rise to the top as real news. They are usually stories that are both political, historical, and personal at a life-or-death nexus, and we gather around them, compelled to watch ourselves be defined and changed by them. One such moment in American history was this capture, trial, incarceration, and release of Gary Powers. As a result, there are many, many books about him. But why not go to the source? Operation Overflight: The U-2 Spy Pilot Tells His Story for the First Time by Francis Gary Powers with Curt Gentry, introduces us to a young man who is too antsy to follow his coal-miner father’s wish for him to be a doctor, so he becomes a pilot, who ends up being recruited by the CIA, essentially being snatched away from his wife for secret training on a brand new, almost invisible plane in the remotest portion of Southern Nevada. From there we follow him to the strange culture of a pilots’ base in Adana, in southern Turkey for illicit, though president-approved overflights of the U.S.S.R. We get the first person account of his capture, imprisonment and release. There is little analysis here, just what happened, how it happened. It’s a picture of the storm, told from the perspective of the eye. Good stuff.

If you want to research further, you’ll have no shortage of material. Currently making the rounds is a lengthy, multi-episode documentary on the Cold War by CNN. One thing the series was critiqued for was the episode that paired McCarthyism and Stalinism. Some argued that in attempting to appear even-handed, it downplayed some of the horrors of the Eastern regimes, equating them with the U.S.’s actions at that time. (People still argue over the numbers, but Stalin killed many, many millions of his own people.) And having been born in San Francisco in the sixties, I know that the liberties I enjoyed were not the same as those enjoyed by my contemporaries in the Eastern Bloc. Both governments did horrible things. But different, horrible things.

This documentary, along with other images, books, and movies on the subject, even when accurate, are, by matter of quantity, inaccurate, because they are brief glimpses of something that spanned decades and continents. From midcentury when the Allies began parceling out bits of Berlin at the end of the second World War, to the day in the late 80’s when the protesters streamed peacefully out of Leipzig and Dresden in a wave that would crest the Wall and lead to its destruction, the Cold War was nothing if not a massive, diverse, and global exercise in the human capacity for duplicitous aggression.

As for whether it matters or not that after next week our first thought of the Cold War may be an image of Tom Hanks looking earnest in a retro hat, maybe all we can do is realize that that space in our minds is precious real estate. And whatever occupies it, we should not confuse the image with the thing itself. As the saying goes, a picture of tree is not a tree.

And how a story is told matters as much as what is told. Not only is a picture of a tree not a tree, but poet Mary Oliver, in her recent book A Poetry Handbook: A Prose Guide To Understanding and Writing Poetry tells us that a “rock” is not a “stone.” Choice of words, and in cinema, images, is crucial to story telling. And whether it is told with a single perspective, as with Powers’ book, or the policeman looking back on his own life, or with many crafted hands such as the Coen brothers, or CNN’s big budgeted crews, these choices affect us. And if I remember the text books of my childhood, the ones that glorified Columbus and had picturesque sidebars of Native Americans without any pesky details about their annihilation, I’m inclined to take it all with a grain of salt, and a half. I don’t know if those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it, or not. But I do think that those who oversimplify the past are condemned to misunderstand that.

I’m hoping this’ll be a great movie. Some movies, even after all of my research still ring true and help me reflect on the era that predates me by just a bit. Alfred Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain, (1966), for example, has an escape sequence that looks like I pictured from my reading. After reading some of Kennedy and Khruschev’s dilemma’s, Failsafe, (1964), with Henry Fonda as a president with his finger on the button, also seems fairly on point, and still gives me the chills. And Das Leben des Anderes is a terrific film. Artfully done, with characters I will never forget. I’ve lived in Berlin and can’t help wishing I could’ve seen it how it was, just for a moment. That film is as close as I will come.

A few books slightly broaden the film’s topic, but I found them of value and recommend them here.

For first-hand, personal interviews, I recommend The Firm: the Inside Story of the Stasi by Gary Bruce, and Stasiland: Stories from Behind the Berlin Wall by Anna Funder.

For an in-depth global and German/American analysis of the minute by minute tipping point during the year the Wall went up, I recommend Berlin 1961: Kennedy, Khruschev, and the Most Dangerous Place on Earth by Frederick

More Blog Posts from Lisa

As of next week, we’ll have another image for the pile. A blockbuster starring Tom Hanks and directed by Steven Spielberg, titled Bridge of Spies.

One nice thing about being a movie fan these days, is that we can see how movies have lives over time. As they stay the same, we watch and re-watch them, seeing how we change around them. Eventually, they may look dated, silly, or even offensive. Alternately, they may point so directly to something we have continued to ignore, we are shamed by their prescience.

Where Bridge of Spies will fall, time will tell.

About a year ago, I began researching a novel that I intend to set in East Berlin in the 1980’s. But I soon found that to understand Berlin in the 80’s, one must understand Berlin in the 70’s, and the 60’s, and that, in fact, if you want to understand the Cold War, you need to understand the hot ones that preceded it. This is a zone writers can get stuck in, as researching becomes its own, fascinating form of procrastination. I finally have made it back to the 80’s, but on the way there, I read a few books that circle the subject matter of an upcoming blockbuster film, Bridge of Spies, so it seemed like a good time to discuss them, almost as a prophylactic, before the film takes its place in your mind as a definitive image of these events. It is not a matter of how much one loves books, or how much one loves movies. It’s just how it is. Once you’ve seen the movie, it becomes very difficult to dislodge the images. I read all the Harry Potter books, but now, Daniel Radcliff’s is the face I see when I think of Harry.

The plot of the upcoming film deals with the downing of a U2 spy plane over Russia, the subsequent capture of its pilot, Francis Gary Powers, and his exchange for a prisoner held in the States, a Russian operative working in the U.S. under multiple aliases, one of which was Rudolf Abel. Hanks plays American lawyer James Donovan, who helped negotiate the exchange. Publicity for the film, with script by Matt Charman and Joel and Ethan Coen, does not credit the first book on my list as a source, though it shares the same title, and subject matter.

Giles Whittell’s non-fiction book, Bridge of Spies A True Story of the Cold War tells the twin tales of Powers and Abel leading to one of the most iconic events of the Cold War, when the two were traded for one another at a popular locale for such swaps, the Glienicke Bridge, which spans the Havel river and connects the Wannsee district of Berlin (under western control during the cold war) with Potsdam (under the control of Eastern Germany at the time.)

Mr. Whittell is Washington correspondent for The Times, and this book is written in straightforward, journalistic prose that reads like a thriller because it is one. If you read on of the three on this list, this is the one.

One of the most troubling points in my research was interviewing a man who had been a high-ranking police officer in East Berlin during the 70’s and 80’s. A criminal investigator for the Volkspolizei. One point he made repeatedly when we spoke was that in the 80’s, they closed all of their cases. All of them, he emphasized proudly. Well, they had informants, both paid and coerced by other means, in every building, pub, workplace and neighborhood in Berlin. They could arrest anyone they wanted for any reason at any time. Of course they closed their cases! But the man, now around seventy, wasn’t exactly boasting. What I came to realize was that he was trying to convey to me that the department was an efficient one. I was an author, asking specific questions about training, development, and execution of the law in practical terms. And he was a professional, proud of the work he did. Of course I empathize with the oppression that was endemic at this time, and we all know of people imprisoned for their beliefs or opposing the government. But human beings commit all kinds of crimes, and there’s no reason to believe that rapists and murderers and thieves disappeared during the Cold War. I had never given much thought to this man, and others like him, who were the ones tracking those people down, facing all the usual difficulties and dangers of police work as the war raged on. Yes, they were an arm of the MfS (Ministry for State Security, or Stasi) but they also had a job to do- or try to do- within their own oppressive system.

The man I spoke with seemed to me somewhat heartbroken that this work had not, in the end, meant, in the end, what he’d hoped it would mean for him. He was strapped financially, had lost his sense of position almost entirely. Twenty-five years after the fact, I think he was still confused by it all, disoriented even. Meeting him was a great reminder to me that important players in history are still human beings. Complex, often conflicted, not easily summarized or pigeon-holed.

One such complicated character, a looming presence in East Germany during the Cold War, and perhaps the best subject of study for those who want a comprehensive sense of the swapping of prisoners throughout the entirety of the era, was Wolfgang Vogel, the East German attorney who brokered most of the important prisoner exchanges, including that of Powers and Abel. (He’ll be played by Sebastian Koch, a German film star American audiences may remember from the film Das Leben des Anderes.) Vogel, like my Policeman, was vilified when the wall came down, but his day-to-day life seems mostly to have been that of a hardworking advocate, capitalizing on the East German government’s poverty to negotiate freedom for some of its most coveted prisoners, which is to say, some of its most oppressed citizens. Spy Trader: Germany’s Devil’s Advocate and the Darkest Secrets of the Cold War by Craig R. Whitney is absolutely crammed with dangerous close calls, nefarious political maneuvers, and nuts and bolts of thousands of exchanges that kept the nearly bankrupt regime from crumbling sooner than it might otherwise have done. Vogel is the main character study, and his counterpart, Donovan, also figures prominently. For a lawyer, or anybody interested in the law, this is a fascinating book.

During the Cold War, information was closely guarded on both sides. In London in the 80’s, underground booksellers would sidle up to someone and whisper: “Spycatcher,” because the book had been banned in the U.K. Even though these days we are overloaded with information, then as now, there are moments that rise to the top as real news. They are usually stories that are both political, historical, and personal at a life-or-death nexus, and we gather around them, compelled to watch ourselves be defined and changed by them. One such moment in American history was this capture, trial, incarceration, and release of Gary Powers. As a result, there are many, many books about him. But why not go to the source? Operation Overflight: The U-2 Spy Pilot Tells His Story for the First Time by Francis Gary Powers with Curt Gentry, introduces us to a young man who is too antsy to follow his coal-miner father’s wish for him to be a doctor, so he becomes a pilot, who ends up being recruited by the CIA, essentially being snatched away from his wife for secret training on a brand new, almost invisible plane in the remotest portion of Southern Nevada. From there we follow him to the strange culture of a pilots’ base in Adana, in southern Turkey for illicit, though president-approved overflights of the U.S.S.R. We get the first person account of his capture, imprisonment and release. There is little analysis here, just what happened, how it happened. It’s a picture of the storm, told from the perspective of the eye. Good stuff.

If you want to research further, you’ll have no shortage of material. Currently making the rounds is a lengthy, multi-episode documentary on the Cold War by CNN. One thing the series was critiqued for was the episode that paired McCarthyism and Stalinism. Some argued that in attempting to appear even-handed, it downplayed some of the horrors of the Eastern regimes, equating them with the U.S.’s actions at that time. (People still argue over the numbers, but Stalin killed many, many millions of his own people.) And having been born in San Francisco in the sixties, I know that the liberties I enjoyed were not the same as those enjoyed by my contemporaries in the Eastern Bloc. Both governments did horrible things. But different, horrible things.

This documentary, along with other images, books, and movies on the subject, even when accurate, are, by matter of quantity, inaccurate, because they are brief glimpses of something that spanned decades and continents. From midcentury when the Allies began parceling out bits of Berlin at the end of the second World War, to the day in the late 80’s when the protesters streamed peacefully out of Leipzig and Dresden in a wave that would crest the Wall and lead to its destruction, the Cold War was nothing if not a massive, diverse, and global exercise in the human capacity for duplicitous aggression.

As for whether it matters or not that after next week our first thought of the Cold War may be an image of Tom Hanks looking earnest in a retro hat, maybe all we can do is realize that that space in our minds is precious real estate. And whatever occupies it, we should not confuse the image with the thing itself. As the saying goes, a picture of tree is not a tree.

And how a story is told matters as much as what is told. Not only is a picture of a tree not a tree, but poet Mary Oliver, in her recent book A Poetry Handbook: A Prose Guide To Understanding and Writing Poetry tells us that a “rock” is not a “stone.” Choice of words, and in cinema, images, is crucial to story telling. And whether it is told with a single perspective, as with Powers’ book, or the policeman looking back on his own life, or with many crafted hands such as the Coen brothers, or CNN’s big budgeted crews, these choices affect us. And if I remember the text books of my childhood, the ones that glorified Columbus and had picturesque sidebars of Native Americans without any pesky details about their annihilation, I’m inclined to take it all with a grain of salt, and a half. I don’t know if those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it, or not. But I do think that those who oversimplify the past are condemned to misunderstand that.

I’m hoping this’ll be a great movie. Some movies, even after all of my research still ring true and help me reflect on the era that predates me by just a bit. Alfred Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain, (1966), for example, has an escape sequence that looks like I pictured from my reading. After reading some of Kennedy and Khruschev’s dilemma’s, Failsafe, (1964), with Henry Fonda as a president with his finger on the button, also seems fairly on point, and still gives me the chills. And Das Leben des Anderes is a terrific film. Artfully done, with characters I will never forget. I’ve lived in Berlin and can’t help wishing I could’ve seen it how it was, just for a moment. That film is as close as I will come.

A few books slightly broaden the film’s topic, but I found them of value and recommend them here.

For first-hand, personal interviews, I recommend The Firm: the Inside Story of the Stasi by Gary Bruce, and Stasiland: Stories from Behind the Berlin Wall by Anna Funder.

For an in-depth global and German/American analysis of the minute by minute tipping point during the year the Wall went up, I recommend Berlin 1961: Kennedy, Khruschev, and the Most Dangerous Place on Earth by Frederick

More Blog Posts from Lisa

RSS Feed

RSS Feed